Famous Psychological Experiments - Milgram Obedience Studies

Milgram was an incredible researcher and scientist

There are two incredibly famous psychological studies (probably the only two that most people could come up with from Psych 101), both run in the 1960s/1970s and due to ethical concerns, unlikely to ever be run the same way again. Even though they’re often discussed in the same breath, one was done incredibly rigorously and repeated countless times by its lead scientist while the other was run once and has never been really repeated. I am talking about the Milgram Obedience Studies and the Zimbardo experiment aka The Stanford Prison Experiment.

This blog post is all about the Milgram Obedience Studies. I’ll add a link out to the Stanford Prison Experiment one when it’s complete.

The Experiment

If you haven’t heard of the Milgram experiment before, please watch this video from actual participants. If you’ve heard of it and never seen it before, it’s also worth watching. I always find it riveting.

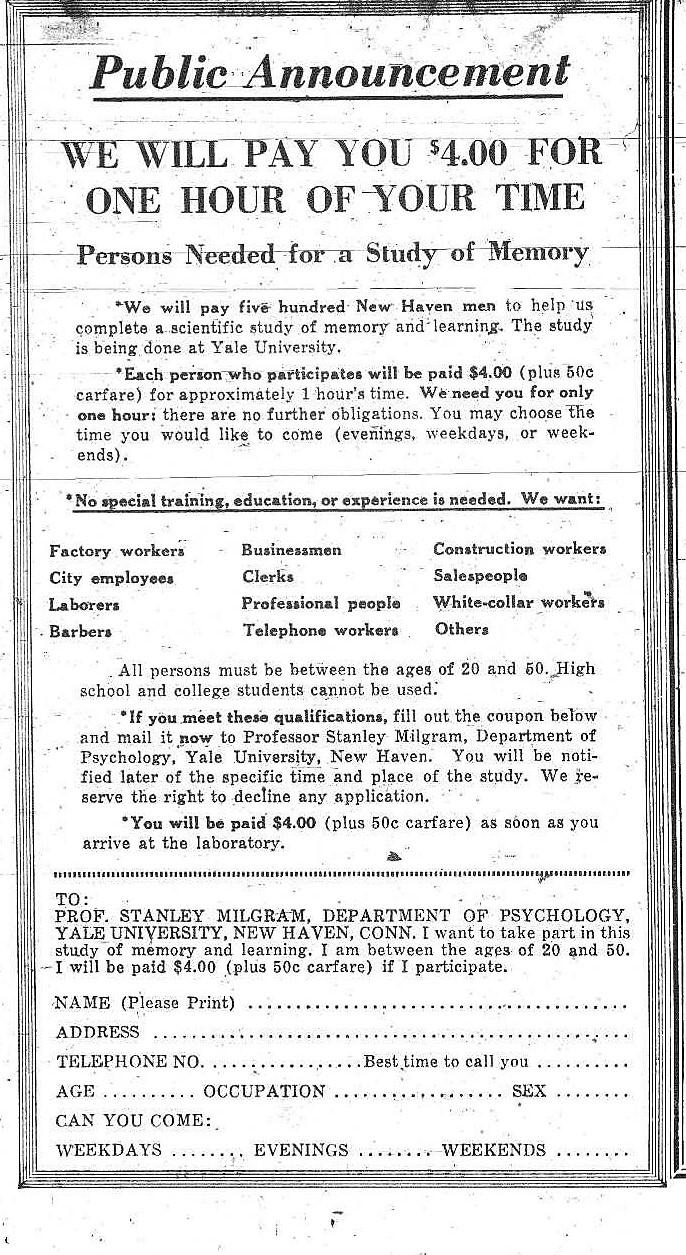

We’re running a memory study. Take 2 people and stick them in a room. One of them will be the teacher and one of them will be the learner. The learner will have to remember various phrases or word pairs, and the teacher will administer electric shocks if they don’t remember them correctly. The teacher is given a sample electric shock to see what it feels like. The electric shocks increase in intensity.

That was all a framing device. The learner is an actor, a heavy-set man pretending to have a heart condition. The shocks are all fake, though they go up to a lethal dosage. The teacher is the only one being experimented on, and the researchers are trying to see how far they’ll go in shocking this person. The learner goes through various stages, yelling and pounding on the wall before going silent. The researcher has a prepared script of 4 “prods” if the teacher wants to stop:

Prod 1: Please continue.

Prod 2: The experiment requires you to continue.

Prod 3: It is absolutely essential that you continue.

Prod 4: You have no other choice but to continue.

Side note: in the original experiment, people made different decisions on each prod 1-3, but on prod 4, everyone who heard it stopped. There’s something about the phrase “no other choice” which gives people self-confidence to push back.

The Results

Everyone assumed in advance that very few people would reach the end of the shock dosages. Milgram did an experiment after the work had been done but before it had been published asking Yale seniors, average adults, or psychiatric residents to guess how many people would administer the highest shock. People suggested that only the “pathological fringe” would go to the end of the shock spectrum. The guesses were on the order of 1-2% regardless of who Milgram asked. In the first experiment, 65% (26/40) subjects went all the way to the maximum shock value.

From The Man Who Shocked the World:

In February 1962, Milgram carried out the prediction exercise with a group of psychiatric residents at Yale before lecturing to them. He described the results in a letter to the social psychologist E.P. Hollander: “The psychiatrists -- although they expressed great certainty in the accuracy of their predictions – were wrong by a factor of 500. Indeed, I have little doubt that a group of char-women would do as well.”

The thing I love about Milgram is that he didn’t stop there. In his original pilot, run with a class at Yale, the learner sat on the opposite side of silvered glass window where you could make out shapes and movement, but not see real detail. But people didn’t want to look at him, so Milgram took this as an experimental condition.

He ran 4 studies, called “the Proximity studies”:

Remote (Experiment 1, Learner in another room, pounds on the wall at 300 volts, at 315 voltes the pounding ends) - 65% went to the end (26/40 went to maximum voltage)

Voice Feedback (Experiment 2, as above, the Learner was in another room but their voice was audible) - 62.5% went to the end (25/40)

Proximity (Experiment 3, Learner in the same room) - 40% went to the end (16/40)

Touch-Proximity (Experiment 4, the Learner only got a shock when their hand was resting on a shock plate, at 150 volts, the Learner was no longer willing to put their hand there and the Teacher had to physically put their hand there) - 30% went to the end (12/40)

Milgram’s book Obedience to Authority is a great read. It reminds me a lot of Things Could Be Better, which recently circulated on Substack. Milgram saw things in the world that didn’t make sense to him and tested them with the tools available. He ran 24 variants.

Some of my favorites:

In the baseline, the Learner is a heavyset “avuncular” man and the Experimenter is kind of thin and severe. What if we swapped the two roles? (Experiment 6 - 20/40)

Let’s make sure that people left to their own devices wouldn’t use the maximum voltage. The teacher can choose any shock level they want. (Experiment 14 - 1/40)

What if there was no experimenter in the room, just a phone number they can call if they want? (Experiment 18 - 10/40)

What if it was all women instead of men? (Experiment 20 - 26/40)

Do people trust that nothing bad will happen because this is at Yale? What if we ran it in a seedy office building in Bridgeport? (Experiment 23 - 19/40)

The Cultural Relevance

There are differing opinions about how much Milgram’s work was actually about understanding the Holocaust. His grant funding requests were about Chinese brainwashing (but this may also have been a guess/reflection of what was getting funded), Milgram was both born Jewish and started practicing later in life, long after the Obedience experiments. But the example that comes up in the same sentence as Milgram’s work almost inevitably is Adolf Eichmann.

In 1960, the year before the experiments started, Adolf Eichmann, one of the major organizers of the Holocaust, was captured by Israeli agents outside Buenos Aires. I highly recommend the book Hunting Eichmann for stories about the capture, including how they dressed him up as a drunk flight attendant to sneak him onto the first El Al flight to South America (ostensibly for a diplomatic occasion). Israeli Shin Bet agents (the equivalent of the FBI) convinced/coerced Eichmann to sign a letter agreeing to be tried in Israel, and was tried by Israel’s attorney general in April 1961. The trial lasted 9 months, had over 100 witnesses, and brought forward the vision of The Holocaust that we still have today. The word “Holocaust” as meaning the massacre of Jews in Western Europe in the 1930s and 1940s also dates to this period.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt covered the Eichmann trial for The New Yorker, and coined the phrase “the banality of evil”. Her columns were later put together into a book, Eichmann in Jerusalem. Eichmann used a variation of the defense used in the Neuremberg trials: he was just following orders. At trial, he did not look like the terrifying Nazi that he must have been in his heyday. He looked like a small, scared bureaucrat in a glass cage and talked about writing railway schedules as if he didn’t know that the trains were full of innocent people going to their deaths. Arendt wrote later in life:

I was struck by a manifest shallowness in the doer which made it impossible to trace the incontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives. The deeds were monstrous, but the doer—at least, the very effective one now on trial—was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither monstrous nor demonic.

These two events, closely matched in time, harmonized. Anyone could commit horrible acts, and you could reproduce this in the lab. Milgram had an exceptional quote about it also.

In a naive moment some time ago, I once wondered whether in all of the United States a vicious government could find enough moral imbeciles to meet the personnel requirements of a national system of death camps, of the sort that were maintained in Germany. I am now beginning to think that the full complement could be recruited in New Haven.

Apologies for the digression, but Eichmann was a terrible person and I’m not letting him escape it even in death. While Eichmann was living in Argentina, he gave a wide ranging set of interviews to Willem Sassen, an ex-member of the SS. The real Eichmann came out in the tapes. Quoting from Deborah Lipstadt in The Eichmann Trial:

[Eichmann] bemoaned the fact that the regime had not killed more Jews and expressed great satisfaction about how smoothly the deportation process had run. He declared that if the official Reich statistician had correctly concluded that “we killed 10.3 million, then I would be satisfied”.

Though the transcripts were available at his trial, the tapes weren’t and there wasn’t clear evidence that Eichmann actually said the things attributed to him. An Israeli film crew recently got access to the full tapes from a German archive, and he was as horrible as people said.

The Criticism

Returning to Milgram’s work, criticism came almost immediately. There were two surprisingly different lines of criticism:

You scarred these people for life!

Why does any of this matter?

Scarring the Participants

Diana Baumrind published a note in American Psychologist in 1964 criticizing the ethics of the experiment, particularly the long-term effects.

Interestingly (and unusually for the time), Milgram had collected follow-up data. From The Man Who Shocked the World:

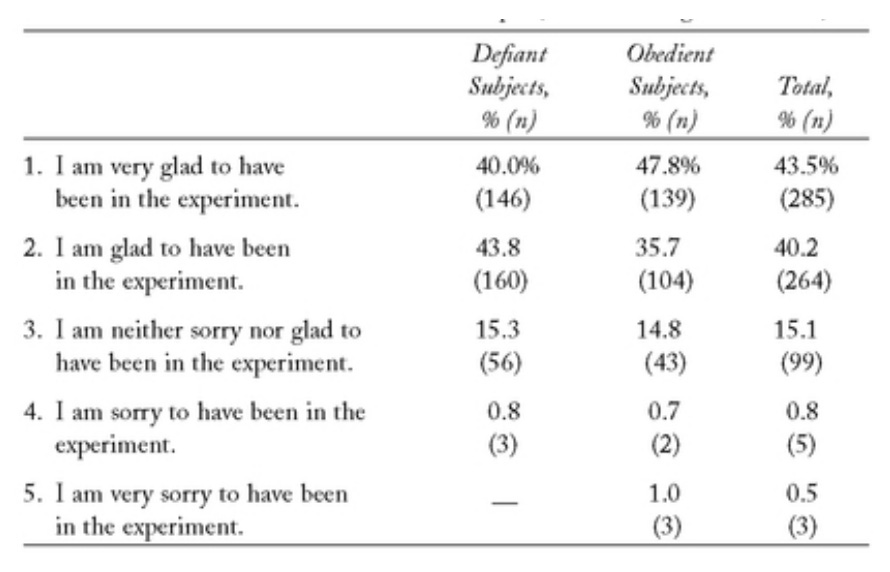

[A]bout six weeks after the conclusion of the experiments, Milgram sent all participants a detailed report about the experimental procedure, its rationale, and some of the main results. Appended to the report was a questionnaire asking the respondents to reflect back on their experience during the experiment.

It went out to 856 participants in the studies, and 92% of them (!) returned them. Only 1.3% of respondents were sorry that they participated.

Three notes:

92% response rate for a mailed survey is incredible. This means you almost don’t have to worry at all about reporting bias. Milgram still didn’t trust it. “Furthermore, Milgram conducted some follow-up analyses to see if respondents differed in any meaningful way from nonrespondents.” The only significant difference was age (below 35 less likely to return the survey).

He also had a psychiatrist do 40 interviews with the people “most likely to have suffered consequences from participation”.

This is six weeks after the end of all of the experiments. It meant that respondents were between six weeks and eleven months out from their experiences.

To me, this is undercut by the lack of debriefing/”de-hoaxing”. Something that was within ethical guidelines at the time but is clearly nuts now is that most people left the experiment not understanding what had happened. They didn’t get informed that the shocks were fake or that the learner was a confederate until they got a letter in the mail up to 11 months later. In Behind the Shock Machine, Gina Perry tracks down a bunch of people who participated in the original study. Some of them never saw the letter and learned the true nature of the study more than 10 years after the study completed! Compare this with the protocol from a modern re-run by Jerry Burger at Santa Clara University: “ I allowed virtually no time to elapse between ending the session and informing participants that the learner had received no shocks. Within a few seconds of the study’s end, the learner entered the room to reassure the participant that he was fine.“

No Theoretical Model

The work was initially rejected by several different journals for having no theoretical model. Blass described his work well as being “phenomenon oriented” rather than “theory based”. I actually think “here is a weird thing that nobody expected” ought to be a publishable result, but I found it much clearer from a line of work that Milgram pursued later in life.

He called them “cyranoids”, which were “a person who does not speak thoughts originating in his central nervous system: rather, the words that he speaks originate in the mind of another person who transmits those words to the cyranoid by means of … a tiny FM receiver with connecting earphones fitted inconspicuously in his ear”. It’s like when Cyrano de Bergerac helps Christian declare his love for Roxanne, with Christian repeating Cyrano’s speech word-for-word.

It’s a neat technique (especially considering this is 1978/1979), but why? Okay, say that people can’t tell when someone is being spoken through as opposed to speaking for themselves. That’s surprising, and does it have any external validity or real use? Does it say anything about who we are as people? Someone ran the experiments recently and they landed with a whimper.

The Obedience experiments are a little bit the same way (as I like to say “interesting, but not useful”).

Modern Replications

I want to point to some modern research done adjacent to Milgram’s work, to show its amazing half-life.

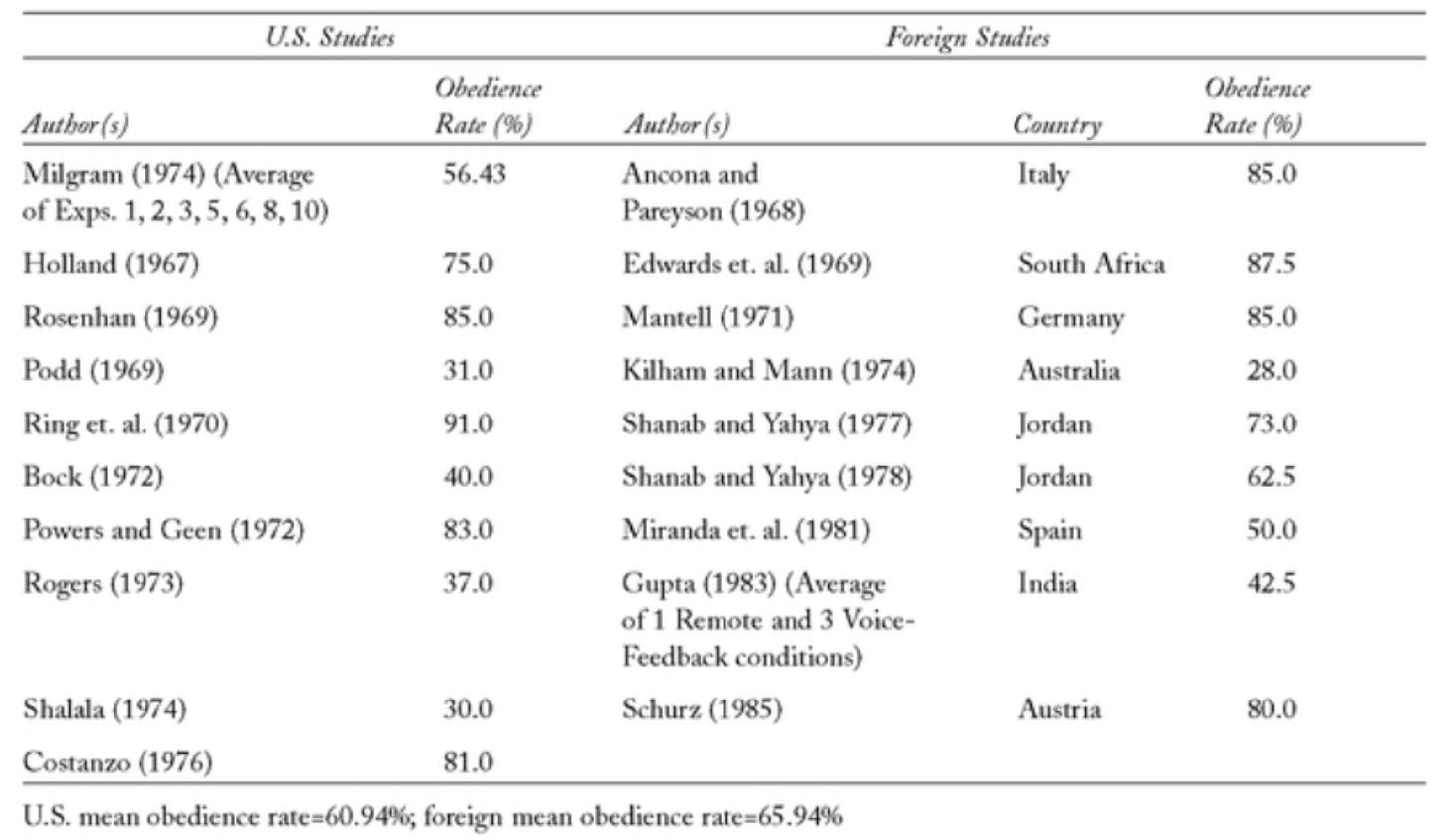

From The Man Who Shocked the World, here is a summary of the persistence of effects across countries. The effects are so stable.

I mentioned it above, but there was an ethical re-run at Santa Clara University in 2008.

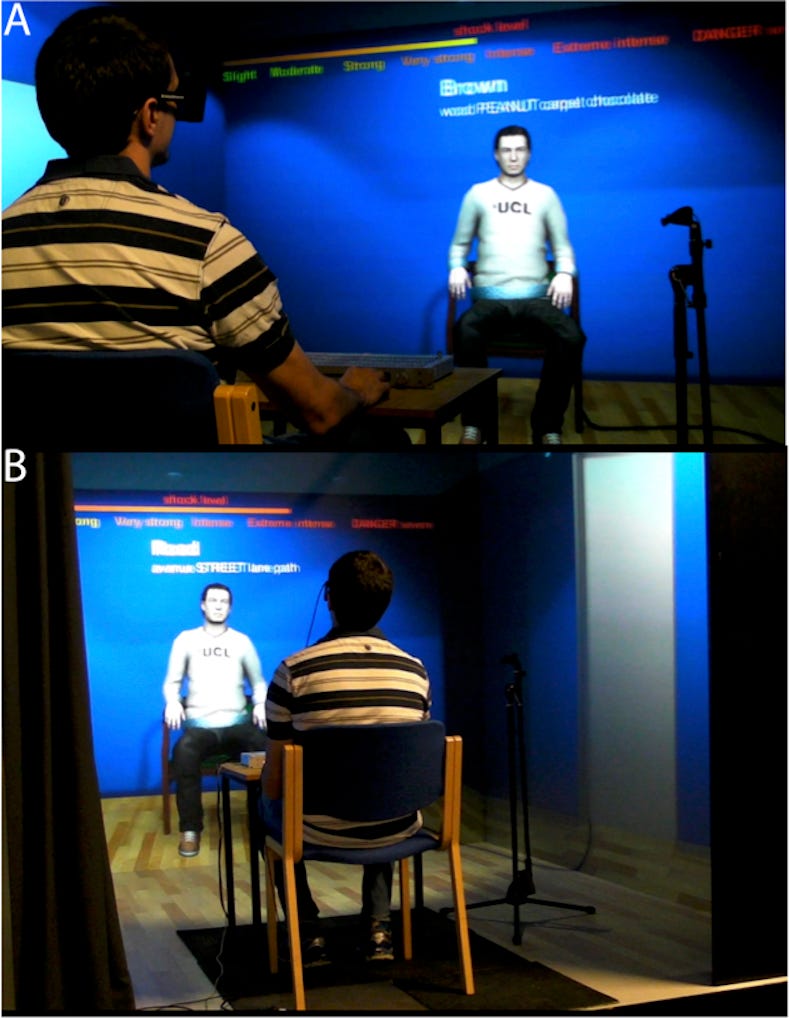

Alex Haslam (who you will hear more about in the Stanford Prison post) did a re-run in Virtual Reality in 2018.

In learning about this, I have to say, this effect is remarkably persistent over time. Milgram did some real science here and it shows!

The Rest of Their Career

Milgram was not a one-trick pony. The Obedience experiments “[made] his name, but cost him his reputation”, according to Gina Perry. He did the experiments at 27 as a young professor at Yale, and bounced around a while before ending up at City University of New York. He did two more experiments that you may have heard of and came up with an interesting third technique worth mentioning.

Six Degrees

Milgram is the one who first found the “small-world” phenomenon, that people are connected by fewer steps than you would have expected. From The Cut:

Funded by a $680 grant, Milgram mailed out brown folders, first to participants in Kansas and, in a later experiment, in Nebraska. Each package contained the name of and basic information about a target person, a roster that participants were asked to add their names to as they came into possession of the folder, and a packet of postcards to be returned to Milgram at each step so he could track folder progress. Participants were asked to give the folder to someone with whom they were on a first-name basis.

Only 26% of the packages made it there, but it gave a convenient quantitative dimension to a feeling that we’ve all had.

Milgram rushed the work out, describing it first in Psychology Today before publishing it several years later in peer reviewed journals.

This entered the public consciousness in 1990 via the play Six Degrees of Separation by John Guare. The game Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon came around in 1994.

Subway Seats

New Yorkers re-discover Milgram’s work on asking strangers for their subway seats every couple of years. It always comes with the same two realizations:

Strangers give up their seats to you, even if you don’t provide a reason, at incredibly high rates.

The askers are so uncomfortable doing it that they often feel physically sick.

Milgram lived in New York and liked quantifying phenomena that he encountered. He also felt incredibly uncomfortable asking people for their seats on the subway.

Lost Letters

Milgram wanted a way to assess feelings on a subject without asking people directly about them. So what he did was lose letters in various places addressed to a variety of different causes and see how often people mailed those lost letters. Students “lost” 100 letters addressed to each of four different groups: Friends of the Communist Party, Friends of the Nazi Party, Medical Research Associates, and Mr. Walter Carnap.

Unsurprisingly, people were much more willing to send mail to people (71 to Walter) and benign causes (72 to Medical Research Associates) than to charged ones (25 to Communists and Nazis).

After proving feasibility, he did a study on racial integration: “Equal Rights for Negroes”, “Council for White Neighborhoods” and “Medical Research Associates” (control). He went to primarily white and primarily black neighborhoods in Charlotte and Raleigh.

He tried to figure out what was going to happen in the 1964 presidential election (Johnson vs. Goldwater) by dropping letters out of an airplane, but it didn’t work. From The Man Who Shocked the World:

Many letters landed in trees, in ponds, and on rooftops. Worse still, some got jammed into the movable parts of the airplane’s wings, putting the pilot and his letter-dropping passenger at risk.

Conclusion

In spite of some ethical issues and the lack of a theoretical model, Milgram found an incredible effect with resonance in the public imagination and tremendous replicability. The guy was a great scientist.

Open Questions

Two variants that I remember hearing about (but can’t find):

I think there was one where people really shocked real animals (to get around the “they know on a subconscious level they’re not really getting a shock” criticism) with similar results.

My brother Jon thinks there’s one where they specifically recruited electricians, who were not willing to give shocks above a minimal level.

I could swear Slate did a re-run of the Subway Seat experiments, but I couldn’t find it either.

Please comment if you know more about any of these.